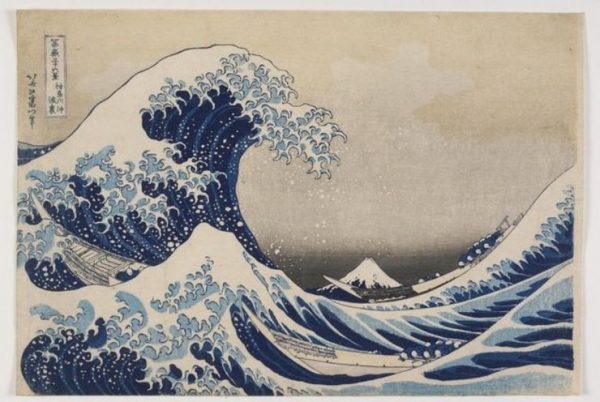

Although the artist typically received all the credit for the prints, there were four people involved with the making of the prints: The artist who drew the prints and decided on the color scheme, the publisher who commissioned and managed the work, the printer who created the final prints and the carver who cut the wood blocks out of cherry, pear or other similar types of wood. The process started with a black-ink wood block and then graduated to multiple-color wood blocks which ultimately produced the final print.

In typical Japanese fashion, the prints were produced by a “division of labor”. The artist first produced a hanshita-e (underdrawing) in accordance with the specifications from the publisher. The publisher would submit the print to the censor, who was either a representative of a wholesale dealer, or in later times, a government official. Once approval had been obtained, the carver prepared the blocks, and then the printer produced the prints.

The artist first sketched the hanshita-e that was exactly the same size as the final print. Over this, the artist placed a thin sheet of strong paper, and traced the outlines of the sketch in black ink. The hanshita-e was pasted face down on a cherry, pear or similar type of wood block, which was then carefully carved to leave the lines of the drawing in relief. The larger areas of the wood block were carved with chisels and knives, while the finer or more complicated areas were carved with small knives. The carvers were expected to serve a 10 year apprenticeship under a single master. The master distributed the work among his apprentices according to their respective abilities, and therefore benefited from the division of labor.

The ink block next went to the printer, who used the ink block to create the color proofs on thin sheets of high-quality paper. He would create 10 or more proofs, depending on the number of colors required for the print. These proofs were then delivered to the artist. For each color to be used in the print, he indicated on the proof where that color should be applied. The color proofs were then sent to the carvers. They pasted each color proof on a wood block, and proceeded to carve away all but the areas indicated for that color.

After leaving the hands of the carvers, the ink and color blocks were sent back to the printers. First, the ink wood block was placed on the print stand. The raised portions of the wood block were painted with black ink. The print paper was carefully aligned, pressed down and rubbed on the ink block with a pressing pad. After the ink impression had been made, the ink block was removed from the print stand, and each color wood block was used in the same way in succession to create the first complete print. Once this specimen proof was approved by the artist, the printing process could begin in earnest. It should be noted that a distinction was made between the ink and color printers. The master printer, like the master carver, divided the labor among his apprentices according to their abilities.

It is estimated that a fine edition of 200-300 prints would take approximately 2 weeks to print. However, lower standards and/or fewer colors could reduce the time drastically. After printing 200 to 300 prints, the wood blocks would require drying out to remove the water absorbed from the print process. In some cases, the wood blocks would need to be completely replaced after the first printing, as the finer lines such as those representing hair would begin to show wear. The paper used was a variety of paper called Hosho, and was made from the bark fibers of a Mulberry tree. Its soft texture allowed good penetration by the pigment and yet was strong enough to resist the rubbing from the pressing pad.