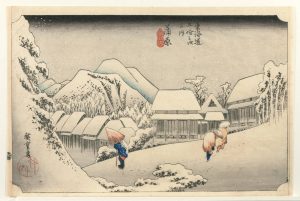

Japan enjoyed something of a travel boom in the late Edo Period (1603-1868). This was no doubt a key impetus behind the famous ukiyo-e landscape series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji” created by Katsushika Hokusai around 1830, depicting the beauty of the iconic mountain from a variety of locations. A short while later, Utagawa Hiroshige came out with his series “Famous Views of the Eastern Capital,” featuring landscapes in Edo (present-day Tokyo). Hiroshige followed in 1833 with the series that became one of the greatest ukiyo-e hits of all time, “Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido Road.”

Inspiring wanderlust

Scenic prints known as meisho-e — “pictures of famous places” — had previously been considered of only secondary interest compared with bijin-ga (“pictures of beautiful women”) and yakusha-e (“actor prints”), but they later joined these subgenres as mainstays in the world of ukiyo-e. In fact, meisho-e are thought to have enjoyed more sustained, long-term sales than portraits of beauties and actors, which tended to rise and fall in popularity with the fickle fortunes of their subjects.

Meisho-e depicting famous spots in Edo were snapped up as souvenirs by samurai returning to their domains after stints in the capital, and prints of scenes along the Tokaido road, the main route between Edo and Kyoto, whetted Edoites’ appetites for travel, whether real or vicarious. Foods associated with each locale tended to be included in the scenes portrayed, adding to the ways in which the prints served like today’s travel guides. The less well-to-do would buy a single print, while some better-off folk would purchase in quantity. For those with the means, complete sets comparable to expensive, lavishly produced modern-day art books could be acquired in back rooms, out of view of authorities who enforced edicts from the shogunate discouraging luxury.

A gift for realism

Hiroshige, whose prints appear more faithful to life than those of Hokusai, used the term shinkei, or “true view,” to describe his works, suggesting the great pride he took in this aspect of his art. The sense of realism he achieved has led many scholars to assert that he must have sketched the places he depicted by accompanying an official shogunate mission to Kyoto in 1832.

Hiroshige found ways to use color, line and perspective, as well as his innate sense of space and composition, to imbue his works with a greater sense of realism. For those accustomed to the conventional meisho-e of the era, laying eyes on aspects of Hiroshige’s works for the first time, including but not limited to his vivid use of color, must have been quite an eye-popping experience, much like a person of our own age accustomed to analog TV seeing an HD or 4K image for the first time. From the vivid sense of the seasons achieved through his use of color to the smile-inducing expressions and mannerisms of his characters, a journey through Hiroshige’s landscape prints is filled with an endless variety of “sights to see.”