Ask anyone who has been to Japan, and they will always remember the ubiquitous yellow tactile paving blocks. As a tour guide, I am often asked what they are. Designed to assist sight-impaired individuals travel solo, Japan’s tactile paving blocks are typically found everywhere, such as stairs, elevators and railroad station platforms. First created and used in Japan in 1965, today they are utilized in more than 20 other countries around the world. And it all began with one man, whose initial goal was to help a friend.

Ask anyone who has been to Japan, and they will always remember the ubiquitous yellow tactile paving blocks. As a tour guide, I am often asked what they are. Designed to assist sight-impaired individuals travel solo, Japan’s tactile paving blocks are typically found everywhere, such as stairs, elevators and railroad station platforms. First created and used in Japan in 1965, today they are utilized in more than 20 other countries around the world. And it all began with one man, whose initial goal was to help a friend.This revolutionary aid of tactile paving is a system of textured ground tiles that indicate potential hazards and direction of travel. Japan’s tactile paving blocks are yellow to allow them to be easily spotted by people with diminished — but not a complete loss of — vision. There are two predominant types of tiles: Those with raised dots indicate caution, while those with long, parallel strips provide directional cues.

Origin

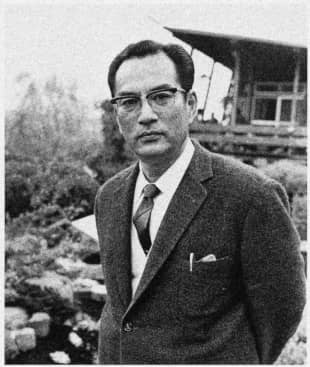

Seiichi Miyake came up with the idea after reportedly seeing a man with a cane almost get hit by a car at an intersection outside his home. The inspiration behind his invention was Braille. By placing various patterns on the ground, he thought that visually impaired people might be able to “read” the pavement with their feet or a cane, much like they would read a book.

After two years and many self-financed prototypes, Miyake settled on a 7×7 “blister” pattern in standard cement, which he believed could be both easily understood and constructed. He named it the tenji block (a nod to the Japanese word for Braille) and dreamed of laying his invention in cities across Japan.

Operating from his home, where he set up the Traffic Safety Research Center, he began a public relations campaign, sending out information on his work, as well as free tenji blocks across Okayama Prefecture and to organizations in Kyoto, Osaka and Tokyo.

However, no orders came.

History

In 1970, Miyake’s luck changed after a faculty member of the Osaka Prefectural School for the Blind laid a tenji block at the platform of Abikocho Station in Osaka, prompting other stations to follow. In the  capital, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government budgeted for 10,000 blocks in Takadanobaba — home to a cluster of facilities for people with visual impairments, including the Japan Federation of the Blind and the Japan Braille Library — making the area the first designated traffic safety model district in the country.

capital, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government budgeted for 10,000 blocks in Takadanobaba — home to a cluster of facilities for people with visual impairments, including the Japan Federation of the Blind and the Japan Braille Library — making the area the first designated traffic safety model district in the country.

With the initiative showing success, tactile paving was introduced by other municipalities across Japan. The Health, Labour and Welfare Ministry announced that a traffic safety guidance system for people with visual impairments was essential in the delivery of its new model city project and Japan National Railways began installing tactile paving at stations nationwide.

In 1985, tactile paving was mandated for broad use nationwide and, in the 1990s, a Welfare Town Development Ordinance that was enacted in each prefecture — starting with Osaka and Hyogo — brought an uptick in installations.

However, the Tenji blocks were initially far from uniform, causing confusion when visually impaired people traveled outside their local area. In 2001, after a series of experiments and in consultation with experts, a national industrial standard for tactile paving was introduced, thereby making compulsory its standard manufacture (a 5×5 blister pattern for hazard tiles and four long bars for directional tiles).

Today

This led to the realization of the global standard from the International Organization for Standardization. The United Kingdom, Australia and the United States became some of the early adopters of the technology, incorporating tactile paving into transportation systems and the urban environment in the 1990s.

Since then, tactile paving has been introduced in almost every continent, and the number of countries adopting it continues to rise.

Today, they can be found on almost all sidewalks and pedestrian crossings frequently used by visually impaired people in Japan. Japanese law requires all buildings of more than 2,000 square meters to have the raised surfaces near potential hazards, such as stairs, escalators, ramps and platforms. There must also be tenji blocks around a railway station’s outdoor area, as well as tiles that stretch from station entrances to manned booths or platforms.

I’ve been hearing so much about these paving blocks, which eventually led me here in the first place. So I finally see what all the hype has been about.